EBITDA normalization is the critical process of adjusting a company’s historical earnings to reflect its true, ongoing profitability for a buyer. This calculation produces Normalized EBITDA; the base figure a buyer multiplies to determine the business valuation. Successfully executed normalization adjustments increase your EBITDA by removing expenses a new, third-party owner will not incur, such as excess owner compensation or personal expenses. By systematically applying these five strategies, you ensure your valuation reflects the maximum economic reality of your business, turning hidden profits into concrete deal value.

Translating Profit into Price

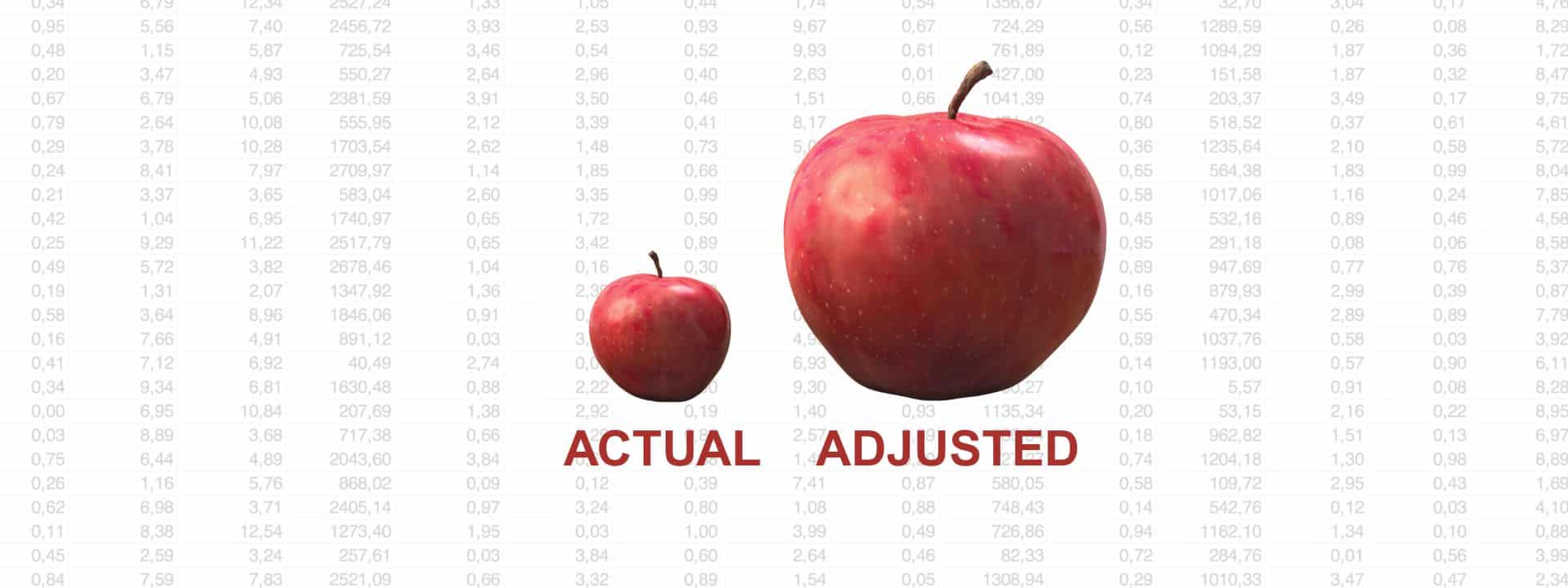

The valuation process begins and ends with your company’s core profitability. Buyers apply an EBITDA Multiple (e.g., 5x or 7x) to your Normalized EBITDA to determine the Enterprise Value. Every single dollar you add back through EBITDA normalization multiplies directly into your final sale price. You must present the cleanest, highest defensible EBITDA calculation possible. This preparation requires identifying every expense that reflects you as the owner, not the business itself.

Removing Owner Discretion

The financials of small- to medium-sized businesses often blur the line between personal and professional expenses. Buyers immediately seek to untangle this complexity.

1. Standardizing Compensation

Owners often pay themselves a salary based on their personal tax strategy or cash availability, rather than the market rate. If your compensation significantly exceeds the cost of hiring a competent third-party CEO, that excess amount is an appropriate normalization adjustment known as a Market Rate Compensation add-back. You must add back the difference between your current compensation and what the business would pay an independent executive. This adjustment immediately shifts a historical expense back into your profit base, boosting your EBITDA.

2. Eliminating Personal Lifestyle Expenses

Personal expenses incurred through the business should also be removed from the P&L. This is one of the quickest, most defensible ways to increase profitability. Buyers search for Non-Operating Expenses like personal vehicle leases, family health insurance, disproportionate travel and entertainment, and club memberships. These are expenses the new owner will not inherit or pay. Systematically identifying and adding back these items results in higher historical earnings.

Recasting Operational Reality

Operational expenses must reflect the costs of running the business under arm’s-length conditions. Buyers will not pay for historical operational inefficiencies or non-market costs.

3. Adjusting Non-Arms-Length Transactions

Many business owners structure real estate or equipment ownership in separate entities, then charge the operating company rent. If the rent expense is significantly above or below the fair market value (FMV), a Related Party Rent/Lease adjustment is required. If you charged above-market rent to extract profits tax-efficiently, adding back that excessive expense becomes a key EBITDA normalization opportunity. You eliminate the historical non-market rent expense, then subtract the actual fair market rent, demonstrating the business’s true operating cost structure.

4. Reclassifying One-Time Extraordinary Costs

Historical financial statements often contain isolated events that skew the true earnings potential. Buyers’ permit add-backs for Non-Recurring Expenses that will not occur again post-acquisition. Examples include one-time lawsuit settlements, unbudgeted facility repairs resulting from a natural disaster, or significant one-off consulting fees from a past reorganization. You must clearly isolate these expenses and document their unique, non-operational nature. This adjustment proves your core business is more profitable than the historical P&L suggests.

Strategic Accounting for Future Value

Strategic preparation involves correcting past accounting decisions that may have understated actual earnings. This ensures your Balance Sheet supports your higher EBITDA claims.

5. Reclaiming Capital Expenses

Owners sometimes expense large, long-term capital investments as immediate repairs and maintenance to minimize tax liability. This aggressive tactic reduces historical EBITDA. EBITDA normalization allows you to identify items such as a one-time server upgrade or a major production line overhaul and treat them as Capital Expenditure rather than Repair Expense. You add back the expense to historical EBITDA, correcting the financial picture. This not only increases the valuation base but also demonstrates to the buyer that the asset base is healthier than previously indicated.

Protecting the Adjustment Schedule

Credibility is the most critical factor in a deal; never be aggressively optimistic. Presenting only add-backs raises immediate red flags. You must proactively acknowledge and include necessary Negative Adjustments that will reduce EBITDA post-sale. For example, if your departure requires the buyer to hire a new, full-time CFO, you must include the estimated salary and benefits for that missing role. Honesty and transparency regarding these adjustments build trust, smooth negotiations, and protect your high valuation claims.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How does the EBITDA Multiple relate to EBITDA Normalization?

The EBITDA Multiple is applied directly to your Normalized EBITDA; therefore, every dollar you legitimately add back through EBITDA normalization increases the final valuation by the size of that multiple (e.g. $100,000 increase x 6x multiple = $600,000 increase in value).

Are non-cash items considered normalization adjustments?

Non-cash items such as depreciation and amortization are not typically considered normalization adjustments in the traditional sense, as they are already excluded from the EBITDA calculation. However, other non-cash charges, such as bad-debt write-offs or unrealized gains/losses, often require specific normalization adjustments if they are non-recurring.

What is the difference between Adjusted EBITDA and Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE)?

The EBITDA vs. SDE differences. Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE) is a metric often used for smaller businesses (with EBITDA less than $1 million) that adds back all owner compensation and benefits, assuming the buyer will operate the business themselves. Adjusted EBITDA (or Normalized EBITDA) is the standard metric used in middle-market M&A, where a reasonable market-rate salary for a replacement manager is deducted from the earnings base.

Partnering with the Windes M&A Team

You have built a high-growth business; now, secure the maximum value for it. Navigating the buyer’s rigorous scrutiny of your EBITDA normalization requires specialized expertise. The Windes suite of M&A strategic services does not just review your financials; it translates your operational success into the language of institutional buyers and financiers. Windes ensures your model is clean, defensible, and fully normalized, preempting the buyer’s skepticism and maximizing your Normalized EBITDA. By strategically preparing and presenting your normalization adjustments, Windes empowers you to maintain control, demonstrate undeniable value, and command the highest possible price at the negotiation table. Don’t leave millions on the table; contact the Windes M&A Team to confidently close the deal.